Kitsilano

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

Kitsilano | |

|---|---|

Vine Street in Kitsilano | |

| Nickname: Kits | |

Location of Kitsilano (in red) in Vancouver | |

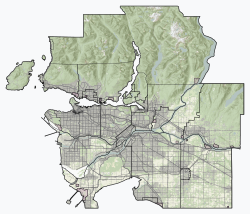

Location of Kitsilano in Metro Vancouver | |

| Coordinates: 49°16′00″N 123°10′00″W / 49.26667°N 123.16667°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| City | Vancouver |

| Named after | August Jack Khatsahlano |

| Area | |

| • Land | 5.46 km2 (2.11 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

• Total | 43,045 |

| • Density | 7,883.6/km2 (20,418/sq mi) |

| Age | |

| • ≤19 | 13.3% |

| • 20-39 | 40.1% |

| • 40-64 | 32.8% |

| • ≥65 | 13.8% |

| First Language | |

| • English | 74.2% |

| • Chinese | 5.6% |

| • French | 2.6% |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Forward sortation area | |

| Area codes | 604, 778, 236, 672 |

| Median Income | $72,839 |

| Population in low-income households | 21.3% |

| Unemployment rate | 5.2% |

| Website | vancouver |

Kitsilano (/kɪtsəˈlænoʊ/ kit-sə-LAN-oh) is a neighbourhood located in the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Kitsilano is named after Squamish chief August Jack Khatsahlano[2], and the neighbourhood is located in Vancouver's West Side along the south shore of English Bay, between the neighbourhoods of West Point Grey and Fairview. The area is mostly residential with two main commercial areas, West 4th Avenue and West Broadway, known for their retail stores, restaurants and organic food markets.[3]

Pre-colonial history

[edit]The area has been home to the Squamish people for thousands of years, sharing the territory with the Musqueam and the Tsleil-Waututh Peoples.[4] All three Nations moved throughout their shared traditional territory, using the resources it provided for fishing, hunting, trapping and gathering.

Post-colonial history

[edit]The name 'Kitsilano' is derived from X̱ats'alanexw, the Squamish name of chief August Jack Khatsahlano.[5][6]

In 1911, an amendment to the Indian Act by the federal government to legalize the unsettling of reserves stated that "an Indian reserve which adjoins or is situated wholly or partly within an incorporated town or city having a population of [more] than eight thousand", could at the recommendation of the Superintendent General be removed without their consent if it was "having regard to the interest of the public" without the need for consent from the reserve's residents.

Subsequently, both provincial and federal governments began the "unsettling of reserves" process, which was the "emptying" of the reserves that "be[came] a source of nuisance and an impediment to progress", or, in other words, the government unsettled reserves for growing cities and potential business ventures; and by the end of 1911[contradictory] the reserve was sold to the Government of British Columbia. At this time in Canadian history, the federal government had already isolated the Indigenous population on to morsels of reserve lands, only to further deprive Indigenous peoples of what the government first thought was negligible land.[7]: 3–10

The Squamish Nation formally surrendered the majority of reserve to the federal government in 1946.[contradictory] Part of the expropriated land was used by the Canadian Pacific Railway who pursued selling the land they had deed to in the 1980s despite the original agreement with the Squamish Nation that they should regain control of the land. This went to court, and in August 2002 the BC Court of Appeals upheld a lower court's ruling in favour of the Squamish.[8] This Indian reserve land is at the foot of the Burrard Street Bridge, called Senakw (commonly spelled Snauq historically) in the Squamish language, and sənaʔqʷ in the Musqueam people's hən'q'əmin'əm' language, where August Jack Khatsahlano lived.

The forced relocation of the Musqueam Nation by the Canadian government resulted in a Musqueam Reserve created on the north arm of the Fraser River.[7]: 3–10 The Squamish Nation was forcibly relocated to reserves on the north shore of Burrard Inlet, currently the cities North Vancouver and West Vancouver, as well as the False Creek Indian Reserve No. 6.[7]: 3–10

False Creek Indian Reserve No. 6

[edit]The False Creek Indian Reserve No. 6, also known as the Kitsilano Indian Reserve, is an Indian Reserve developed by the colonial government in 1869. The reserve is located on the former site of a Squamish village, known as "sən’a?qw" in hən’q’emin’əm’, the language of the Musqueam people, and as "Sen’ákw" in Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim, the language of the Squamish people. Inside the reserve there was a large longhouse that housed families, held potlach ceremonies, and became a central point of trade. The land appealed to its residents and attracted settlers by providing access to natural resources.[7]: 3–10 It served as an important fishing area where inhabitants could set up tidal weirs of vine maple fencing and nettle fibre nets to catch fish.[9] Additionally, the Squamish people cultivated an orchard as well as cherry trees on this land.[7] Between 1869 and 1965, as the development of railway lines drew attention to the reserve, the Burrard Street Bridge and various leases began to occupy the reserve land. The land set aside for the Squamish people was continually appropriated until it was completely sold off. After decades of legal proceedings, the Squamish Nation reclaimed a small amount of the reserve land in 2002.[10][11][12]

Settler history

[edit]

First industry and development

[edit]Most of the area now known as Kitsilano was within the boundaries of Vancouver when it was incorporated in 1886. What is now 16th Avenue was Vancouver's southern boundary, and its western boundary was what is now Trafalgar Street.[13]

Jerry Rogers began logging in the area in 1867 at Jerry's Cove, later known as Jericho.[14] By 1880 the eastern section of Kitsilano was logged off. In 1882 Sam Greer pre-empted 160 acres on the Kitsilano waterfront and with his family began farming it. In 1884, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) manager William Van Horne was negotiating to extend the CPR right of way along the waterfront to what is now Trafalgar Street.[15] That land, and Greer's farm, was included in the 6000 acres granted by the provincial government to the CPR in 1891. Greer was forced out but the beach retained his name.[16] In 1901, the name "Kitsilano" became the official designation, as suggested to the CPR (who were considering building a hotel at the beach) by postmaster Jonathan Miller.[17]

The English Bay Cannery operated at the foot of Bayswater Street from 1898 to 1905.[18]

In 1907, several Kitsilano streets were renamed because they duplicated names in other parts of the city. The new names, some inspired by battles, were Alma Road (formerly Campbell Street), Waterloo Road (Lansdowne Street), Balaclava Road (Richard Street), Blenheim Road (Cornwall Street), Trafalgar Road (Boundary Street) and Point Grey Road (Victoria Street).[19]

The British Columbia Electric Railway Company expanded passenger service to Greer's Beach in 1905 with a streetcar line across the railway trestle over False Creek.[20] A line along 4th Avenue to Alma Road in 1909 resulted in the blocks north of 4th between Blenheim Street and Alma being completely developed as a residential neighbourhood within a year.[21]

Kitsilano was the site of the second Sikh temple to be built in Canada, a few years after the first opened in Golden in 1905.[22] Opened in 1908, the temple served early South Asian settlers who worked at nearby sawmills along False Creek at the time.[23] The Second Avenue Gurdwara served a community numbering around 2000. The building was sold in 1970 to raise money to build the Ross Street Gurdwara in southeast Vancouver.[24]

The influence of Greek immigrants to Kitsilano can still be seen among the businesses along Broadway west of Macdonald. Residents of Greek origin in Vancouver numbered around 3000 in the early 1960s, but were estimated to be as many as 13,000 in 1973. They tended to settle near the Greek Orthodox church (now Kitsilano Neighbourhood House) at 7th and Vine.[25]

The area was an inexpensive neighbourhood to live in the 1960s and attracted many from the counterculture from across Canada and the United States and was known as one of the two hotbeds of the hippie culture in the city, the other being Gastown. However, the area became gentrified by 'yuppies' in subsequent decades. Close proximity to downtown Vancouver, walking distance to parks, beaches and popular Granville Island has made the neighbourhood a very desirable community to live. One of the main concert venues in the city in the days of the counterculture was the Soft Rock Cafe, an all-ages coffee house and music venue near 4th and Maple which operated from 1976 to 1984.[26] Further west, Rohan's Rockpile was another 1970s music venue.[27]

One remaining artifact of the 1960s is the Naam Cafe at 4th and Macdonald, providing vegetarian, vegan, and natural foods. The area is also known for having the first of certain kinds of restaurants, such as the California-style Topanga Cafe, destroyed by fire in 2018.[28] Two of the first neighbourhood pub licenses in Vancouver are still located on 4th Avenue - Bimini's at Maple and Darby D. Dawes at Macdonald.

Activism

[edit]Greenpeace held meetings at Kits Neighbourhood House in 1974 - 1975 when it opened an office on 4th Avenue and Maple, sharing the space with the Society Promoting Environmental Conservation (SPEC).[29]

The first membership meeting of the Green Party of British Columbia was held at the Museum of Vancouver in 1983.[30] The party office was originally located in the home of longtime party leader Adriane Carr and her husband Paul George on Trafalgar Street, near 2nd, in early 1983, before being moved by the summer of that year to offices near Broadway and Cypress, which also became the first offices of the Green Party of Canada.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]Like all of Vancouver, Kitsilano is located in traditional Coast Salish territory. The land that is currently known as Kitsilano has been shared by the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Watuth peoples since time immemorial.[7]: 3–10 Thus, their traditional place names are valuable descriptors of this landscape.[7]: 3–10 The area that is currently known as Point Grey is traditionally known as Chitchilayuk.[7]: 3–10 Beaches now known as Spanish Banks is traditionally known as Pookcha, Jericho Beach is traditionally known as Eyalmo and E-Eyalmo, and Kitsilano Beach is traditionally known as Skwa-yoos.[7]: 3–10 The area that is currently Sasamat Street was once known as Kokohpai, while the area of Bayswater Street was called Simsahmuls.[7]: 3–10

Kitsilano is located in the West Side of Vancouver, along the southern shore of English Bay, with Burrard Street as the neighbourhood's eastern boundary, Alma Street its western boundary, and 16th Avenue its southern boundary.

Adjacent neighbourhoods include the West End northeast across the Burrard Bridge and False Creek, Fairview directly to the east, Shaughnessy to the southeast, Arbutus Ridge directly south, Dunbar-Southlands southwest, and West Point Grey directly west.

Demographics

[edit]As of 2016, Kitsilano has 43,045 people. 13.3% of the population is under the age of 20; 40.1% is between 20 and 39; 32.8% is between 40 and 64; and 13.8% is 65 or older. 74.2% of Kitsilano residents speak English as a first language, 5.6% speak a Chinese language, 2.6% speak French and 0.2% speaking hən'q'əmin'əm. The median household income is $72,839 and 14.7% of its population lives in low-income households. The unemployment rate is 5.2%.[1]

| Panethnic group |

2016[31] | 2006[32] | 2001[33] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | ||||

| European[a] | 33,440 | 78.21% | 33,450 | 82.83% | 33,595 | 85.2% | |||

| East Asian[b] | 4,690 | 10.97% | 3,850 | 9.53% | 3,485 | 8.84% | |||

| South Asian | 1,075 | 2.51% | 655 | 1.62% | 590 | 1.5% | |||

| Indigenous | 735 | 1.72% | 480 | 1.19% | 345 | 0.87% | |||

| Southeast Asian[c] | 720 | 1.68% | 500 | 1.24% | 335 | 0.85% | |||

| Latin American | 700 | 1.64% | 505 | 1.25% | 255 | 0.65% | |||

| Middle Eastern[d] | 485 | 1.13% | 305 | 0.76% | 320 | 0.81% | |||

| African | 400 | 0.94% | 310 | 0.77% | 250 | 0.63% | |||

| Other/Multiracial[e] | 510 | 1.19% | 330 | 0.82% | 255 | 0.65% | |||

| Total responses | 42,755 | 99.33% | 40,385 | 99.48% | 39,430 | 99.52% | |||

| Total population | 43,045 | 100% | 40,595 | 100% | 39,620 | 100% | |||

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | |||||||||

Culture & recreation

[edit]The Museum of Vancouver has gained several pieces of Northwest Coast art from Indigenous artists. Much of the work is displayed in a wide variety of mediums to showcase the Indigenous culture that surrounds this city.[34]

Kitsilano is home to a number of Vancouver's annual festivals and events:

- Each June, Greek Day is an annual street festival celebrating Greek culture and cuisine along several blocks of Greek West Broadway, which is Vancouver's Greektown.

- Vanier Park is home to Bard on the Beach, the outdoor Shakespeare festival running from June to September.

- The Celebration of Light fireworks competition is held mid-summer on the waters of English Bay between Vanier Park and the West End.

- The Khatsahlano Street Party is held on 4th Avenue on a July Saturday.

Parks and beaches

[edit]Kitsilano is home to 17 parks, which include six playgrounds, an off-leash dog park, and Kitsilano Beach, one of Vancouver's most popular beaches.[35] Along with the beach itself, Kitsilano Beach Park also contains a franchise restaurant, Kitsilano Pool, and the Kitsilano Showboat. The Kitsilano Showboat, operating since 1935, is essentially an open-air amphitheatre with the ocean and mountains as a backdrop. It is located on the south side of the Kitsilano Pool along Cornwall Avenue. Until being damaged by fire in 2023[36], it hosted free performances from local bands, dance groups, and other performers all summer long, its main goal being to entertain residents and tourists, showcasing amateur talent. Beatrice Leinbach, MOC, or "Captain Bea," played a role in maintaining the showboat since the mid-1940s. As of 2006, she was the president of the non-profit Kitsilano Showboat Society.[37]

As of September 2018, there was an attempt to reconcile with the Indigenous communities whose land was taken during the expansion of Vancouver. By renaming the beaches and parks, one of which included Kitsilano Beach, Stuart Mackinnon park board chairman was going to work with the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations to rename those areas after their original Indigenous names. However, the Indigenous community replied by saying the original areas were not named previously, because they were only forests before colonization. As of today no beaches or parks, including Kitsilano Beach have been renamed in the hən'q'əmin'əm' (Musqueam Halkomelem) or Skwxwú7mesh Snichim (Squamish language).[38]

Vanier Park is another one of Kitsilano's most popular parks, and is the location of the Museum of Vancouver, the H. R. MacMillan Space Centre, the Vancouver Maritime Museum, the Vancouver Archives, and the Vancouver Academy of Musicas well as the public art installations Gate to the Northwest Passage by artist Alan Chung Hung and "Freezing Water #7" by Jun Ren.[39][40]

Buildings

[edit]Landmark buildings in Kitsilano include the Burrard Bridge, a five-lane, Art Deco style, steel truss bridge constructed in 1930-1932 connecting downtown Vancouver with Kitsilano via connections to Burrard Street on both ends, as well as several historic sites such as the Museum of Vancouver and H. R. MacMillan Space Centre, St. Roch National Historic Site of Canada, Kitsilano Secondary School and the Bessborough Armoury. Kitsilano Neighbourhood House at 7th Avenue and Vine Street combines the 1909 Hay House and a former Greek Orthodox church built in 1930 and now functions as a neighbourhood centre offering childcare, a performance/meeting hall and seniors' housing.[41] St. James Community Square on 10th Avenue at Trutch, incorporating the former St. James church, with meeting spaces, a daycare, gym, multi-purpose rooms and a performance venue, Mel Lehan Hall,[42]is a hub for artists, activists and community groups of all kinds.[43]

Busy Macdonald Street and some quiet, leafy adjoining streets still have some 1910s–1920s craftsman houses that cannot be found anywhere else in Vancouver.[44] According to Exploring Vancouver, an architectural guide to the city:

Kitsilano developed as a less expensive suburban alternative to the West End. Endless rows of developer-built houses lined the grid of streets, their gabled roofs picturesque and not boring. Many (...) resemble West End houses of preceding years, but have the wider proportions, broad verandahs, and wood brackets popularized by the newer and trendier California bungalow.

— Harold Kalman, Ron Phillips & Robin Ward, Exploring Vancouver

Government

[edit]Kitsilano is situated within the Canadian federal electoral districts of Vancouver Quadra[45] and Vancouver Centre,[46] currently held by Joyce Murray and Hedy Fry, respectively. Both are members of the Liberal Party of Canada. Provincially, Kitsilano lies within the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia electoral districts of Vancouver-Point Grey, Vancouver-Fairview, and Vancouver-False Creek.[47] Vancouver-Point Grey is currently held by David Eby of the BC NDP, Vancouver-Little Mountain by Christine Boyle, and Vancouver-South Granville by Brenda Bailey, also BC NDP members.

Notable residents

[edit]Kitsilano is the current or former home of a number of notable residents including former Squamish chief August Jack Khatsahlano (whom the city is named after), environmentalist David Suzuki, writers William Gibson and Philip K. Dick, actors Ryan Reynolds, Jason Priestley, and Joshua Jackson, ice hockey players Trevor Linden and Ryan Kesler, and comedian Brent Butt.

Other current and former residents of Kitsilano include:

- Robin Blaser, poet

- George Bowering, author

- Sven Butenschön, former ice hockey player

- Chelah Horsdal, actress

- Gregory Henriquez, architect

- Eric Johnson, actor

- Peter Kelamis, actor, comedian

- Tinsel Korey, actress

- Major J.S. Matthews, first city archivist

- Frank Palmer, businessman, advertising executive (DDB Canada)

- Evelyn Roth, artist

- Michael Saxell, songwriter, musician

- Jack Shadbolt, artist

- Jared Slingerland, producer, musician

- Spirit of the West, folk music group

- Mark Vonnegut,[48] pediatrician, memoirist, son of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

- Jeff Wall, artist

- Chip Wilson, founder of Lululemon

- Finn Wolfhard, actor, musician, voice actor, filmmaker

See also

[edit]- Seaforth Peace Park

- Senakw

- Squamish Nation

- List of neighbourhoods in Vancouver

- List of Squamish villages

Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Kitsilano; Community Statistics" (PDF). vancouver.ca. Government of the City of Vancouver. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Kalman, Harold (1974). Exploring Vancouver. Vancouver, B.C.: University of British Columbia. p. 181. ISBN 0-7748-0028-3.

- ^ "Kitsilano". Areas of the city. City of Vancouver. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "The Kitsilano Agreement". Squamish Nation. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Matthews, James Skitt (2011). Narrative of Pioneers of Vancouver, BC Collected During 1931-1932: Early Vancouver (PDF). Vol. 1. Vancouver. pp. 21–22.

Professor Charles Hill-Tout claimed on May 8, 1931, that he changed the local name, Greer's Beach, to a more appropriate name, Kitsilano, a modified version of the hereditary name of one of the Squamish chiefs.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kluckner, Michael. "Kitsilano and Arbutus Ridge". The Greater Vancouver Book. DiscouverVancouver.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barman, Jean (Autumn 2007). "Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver" (PDF). The British Columbian Quarterly (155). BC Studies: 3–30. doi:10.14288/bcs.v0i155.626. Retrieved 2018-10-30 – via UBC Library.

- ^ "Kitsilano land belongs to natives, appeal judges agree". 2010-02-14. Archived from the original on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ "Historic Kitsilano Northeast Map Guide" (PDF). Vancouver Heritage Foundation. 2014.

- ^ de Trenqualye, Madeleine. "The History of the Kitsilano Indian Reserve" (PDF). Vancouver Historical Society. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ "Mapping Tool: Kitsilano Reserve". Indigenous Foundations. The University of British Columbia. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ "Item : MAP 859 - Plan showing parcels 'A', 'B' & 'C' : Kitsilano Indian Reserve, No. 6 of the Squamish band, Vancouver, B.C." City of Vancouver Archives. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Davis, Chuck (1976). The Vancouver Book. North Vancouver, B.C.: J.J. Douglas Ltd. p. 326. ISBN 0-88894-084-X.

- ^ Davis, Mooney, Chuck, Shirley (1986). Vancouver An Illustrated Chronicle. Windsor Publications. p. 19. ISBN 0-89781-176-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, Mooney, Chuck, Shirley (1986). Vancouver An Illustrated Chronicle. Windsor Publications. p. 26. ISBN 0-89781-176-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, Chuck (1976). The Vancouver Book. North Vancouver, B.C.: J.J. Douglas Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 0-88894-084-X.

- ^ "Kitsilano is its new name". The Province. July 16, 1901.

- ^ "English Bay Cannery". From Tides to Tins. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ "Sewer into English Bay". Daily News Advertiser. Vol. XL, no. 122. May 22, 1907.

- ^ Davis, Chuck (1976). The Vancouver Book. North Vancouver, B.C.: J.J. Douglas Ltd. p. 327. ISBN 0-88894-084-X.

- ^ Davis, Chuck (1976). The Vancouver Book. North Vancouver, B.C.: J.J. Douglas Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 0-88894-084-X.

- ^ "Sikhs celebrate history in Golden - The Golden Star". www.thegoldenstar.net. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- ^ "First Sikh Temple • Vancouver Heritage Foundation". Vancouver Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- ^ "Canada's First Sikh Temple". B.C. An untold history. Knowledge Network. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ Rossiter, Sean (April 26, 1973). "City's Greeks labor in profit motive". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Lawrence, Grant (5 July 2017). "Kitsilano's legendary Soft Rock Café remembered". Vancouver Is Awesome. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ Spaner, David (August 5, 2007). "The 4th Avenue revolution revisited". The Province.

- ^ "Fire that destroyed Kitsilano's Topanga Cafe ruled accidenta". CBC News. July 9, 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ "Greenpeace & SPEC's Kits House Origins". Kits Neighbourhood House. 24 September 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

- ^ "100 join B.C.'s new Green Party". Vancouver Sun. February 28, 1983.

- ^ Open Data Portal, City Of Vancouver (2018-04-10). "Census local area profiles 2016". opendata.vancouver.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Open Data Portal, City Of Vancouver (2013-03-25). "Census local area profiles 2006". opendata.vancouver.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Open Data Portal, City Of Vancouver (2013-03-25). "Census local area profiles 2001". opendata.vancouver.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "About Us – Lattimer Gallery". www.lattimergallery.com. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ "Kitsilano area parks". Vancouver parks, gardens and beaches. City of Vancouver. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ Ryan, Denise (April 23, 2023). "Kitsilano Showboat in Vancouver badly damaged by fire". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ^ Hughes, Fiona (5 August 2004). "Kits Showboat an enduring tradition". The Vancouver Courier. Lower Mainland Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 30 May 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ "Park board votes to consider Indigenous names for Vancouver parks". Vancouver Sun. 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ "Gate to the Northwest Passage". Public Art Registry. City of Vancouver. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "Artwork Details: Freezing Water #7". Artsfinder. Vancouver Park Board. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ "Kits Neighbourhood House". Places That Matter. Vancouver Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ "Our Story". St. James Community Square. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ The Rogue Folk Club https://www.roguefolk.bc.ca/. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kalman, Harold; Phillips, Ron; Ward, Robin (1993). Exploring Vancouver. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774804103 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ "Vancouver Quadra". Maps Corner. Elections Canada. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ "Vancouver Centre". Maps Corner. Elections Canada. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ "Electoral District Maps (Redistribution 2008)". Electoral Maps / Profiles. Elections BC. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ Vonnegut, Mark (1975). The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-543-9.

External links

[edit] Kitsilano & Granville Island travel guide from Wikivoyage

Kitsilano & Granville Island travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Kitsilano at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kitsilano at Wikimedia Commons- City of Vancouver Neighbourhood Profile

- Kitsilano page, Vancouver Then and Now website, comparisons of older photos with modern locations